This is a summary of the first lecture in a series of lectures on the history of Western Philosophy put on by the Teaching Company. I wanted to preserve these summaries from the 2nd edition of this course because it is out of print; the Teaching Company now publishes the 3rd edition of the course which you can obtain at www.thegreatcourses.com.

This first lecture on the problems and scope of philosophy is presented by Prof. Michael Segrue, who is a Prof. of History at Ave Maria University.

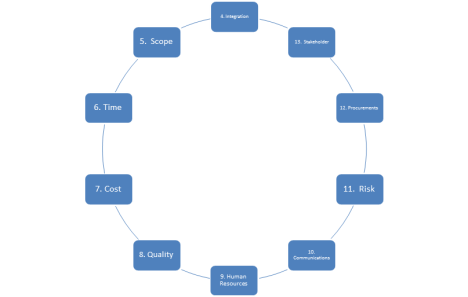

1. The terminology of philosophy—nine terms to understand

The word philosophy comes from two Greek words, the “φιληο” (phileo) meaning “to love” or “to befriend” and “σοφία” (sophia) meaning “wisdom. Philosophy is true to its etymological roots, because it is indeed a love of wisdom or a passion for knowledge which goes beyond practical or utilitarian concerns.

The philosophical tradition of the West is a more or less coherent philosophical tradition with a common set of problems or issues under consideration, and a similar set of technical vocabulary which we use to discuss philosophical topics. Let’s start by considering this series of technical terms now in order to avoid confusion later on.

The first term is that of physics. By physics, we mean a theory of nature; it’s our way of explaining the world around us which we perceive through our senses. It’s the world which ranges from the familiar objects and their components which can be perceived through many senses (tables, chairs), to the larger, faraway objects which we can only perceive through our sense of vision (stars, planets). Physics also encompasses the theory of time and space in which these objects exist.

The second term is that of metaphysics. Metaphysics derives from the Greek

words μετά (metá) (“beyond”, “upon” or “after”) and φυσικά (physiká) (“physics” or “nature”). It is the description of entities which exist independently of space and time such as ideas, or spiritual entities such as angels or God (if you are a religious believers) that are outside of our immediate, everyday experience. It is the inquiry and consideration of things that outside of the realm of nature, which is the domain of physics.

The third term is ontology, which is a highly technical term in philosophy, but it could be simply defined as “speech about beings”. It is a branch of philosophy which allows us to analyze and think about the kind of existence that things have. We can say that God exists in a different way and on a different plane than everyday human beings. In addition, human beings have a set of rights that everyday objects don’t have. God, human beings, and physical objects are different kinds of beings; another more technical way of saying this is that they are all ontologically distinct classes of beings. They have a different status and a different hierarchy. There are different kinds of reasoning we need to apply to them, and differences in the way we apprehend them.

The fourth term is logic. Although this may be a little intimidating when you first encounter it in philosophy, but it is simply a system of rules for deriving true inferences. It says that if you start out with true premises, and follow the rules of logic, you will always draw true inferences. It’s not as complicated as you might have thought.

The fifth term is epistemology, which is another highly technical term in philosophy, comes from the Greek word ἐπιστήμη (epistēmē), meaning “knowledge, understanding”, and λόγος meaning “study of”). It is the speech or reasoning we use when discussing knowledge itself. We are thinking about knowledge or about thinking itself. What kinds of knowledge can we have of different types of things? Our knowledge of mathematics is different from our knowledge of scientific facts such as the boiling point of water, which in turn is different from our knowledge of right and wrong or our knowledge of the way governments ought to be organized. When philosophers engage in epistemology, what they are really trying to do is to clarify their own thoughts and those of other people to eliminate confusions that may have crept into their thinking by using a detailed analysis of how thinking works. It is a means for philosophers to be able to think clearly about various issues.

The sixth term is psychology. Epistemology is the philosophy of what is known, but psychology is philosophy of the knower, that is, the one who is doing the knowing. All of the philosophers of the Western philosophical tradition have a certain concept of the human mind or consciousness. Different philosophers have different concepts of the mind or psychology. Plato had one particular philosophy of mind, and he organized that philosophy of mind or the soul in relationship to the problem of how that mind apprehends mathematical knowledge. The philosophers of the 17th and 18th century on the other hand put together an alternative conception of philosophical psychology, which addressed their differing concerns with respect to epistemology which had to do with the rise of modern science.

Beyond the philosophy of mind, there are three related disciplines.

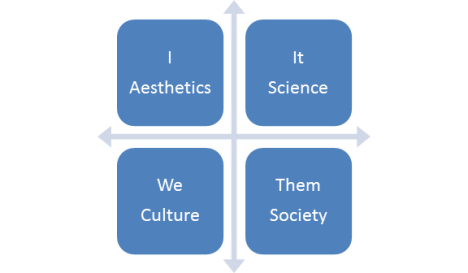

The seventh term is that of aesthetics, the theory of the beautiful. Is the beauty of an object within the object that is being observed or is it in the mind that perceives that beauty? What is the relationship between what it is perceived to be beautiful and that which we judge to be right or wrong? The branch of philosophy called aesthetics takes these various thoughts about beauty and tries to weave them into a harmonious whole.

The eighth term is that of ethics, which inquires into our judgments of what is right or wrong, over our certainty about what we ought or ought not do. What does it mean to engage in actions which are appropriate to a human being? How can we improve the way we behave? It discusses the part of human beings which are not necessarily the same as in animals, and are thus partially outside of the realm of nature. It discusses the choices of human beings, and the judges and values they use when making those choices.

The ninth term is that of politics or political theory¸ which is connected to the study of ethics, studies the city or society in which people live. Both ethics and politics investigate what is good or righteous, but on a different human scale. Ethics discusses what is good or righteous at the level of an individual, while political theory discusses what is good at the level of the society as a whole.

2. The Problems of Philosophy—Two Rivers, One Stream

The concerns addressed during the history of philosophy are remarkably small, as covered by the nine philosophical terms listed above, compared to the enormous diversity and richness of the traditions from which these philosophies emerged, and the vast amount of time over which they developed.

The history of philosophy goes back over thirty centuries, and to go back to the beginning of that history as the first lectures in this series will do, it will require an imaginative leap. The early philosophers in the ancient world of course did not have access to the technology we do, but more importantly didn’t bring many of the same presuppositions to the topic that we do. They lived in a world full of myths and imaginative stories which took the place of rational explanations for things.

If you are willing to make that intellectual and empathetic leap into the minds of the ancients, you will find it easier to absorb the contents of their philosophical debates.

The history of early philosophy can be seen through the answer to the question from ontology, “what is” or “what exists?” There are basically two answers to this question.

A. Nature only

This answers says that there is only the material world, and there is no supernatural or non-physical realm beyond it. As the pre-Socratics would have put it, there are only atoms and the void, and nothing else. The philosophers that believe in this answer to the ontological question “what exists” are those that belong to materialistic interpretations of the world and are called philosophical materialists or naturalists.

This philosophical tradition goes from the pre-Socratics all the way through to that of modern science in the Enlightenment.

B. Nature + something else

An alternative answer to the question “what exists” is that nature exists plus some other world or realm that is external to space and time. In the Western philosophical tradition, an example of this realm is Heaven, which for believing Christians, Jews, and Muslims contains God, the angels, and the souls of human beings that used to live in the material world.

In addition to the belief in Heaven in the Western religious tradition, there is the Greek philosophical tradition of belief in another world beyond that of immediate sense perception, and that is the created by Plato in the world of the Forms, which could be considered analogous to the Christian Heaven in the sense that its significance informs the various objects in our material world. It is a place of pure ideas and pure thought, that is purer than this world where things change and come into and out of existence.

The “two worlds” metaphysical approach goes from Plato all the way through to the tradition of the three Abrahamic faiths. This second world is of enormous significance and contains our source of virtue and moral standards, and justifies good actions.

These two answers to the question “what exists” are therefore, form the two major strata in the philosophical bedrock of the Western philosophical tradition. Which answer a philosopher chooses to this ontological question will inform that person’s views on other philosophical questions such as ethics, politics, and aesthetics, etc.

3. The History of Philosophy—Two Strands, One Braid

Besides the conceptual relationships between the various schools of philosophy, there is the historical development of these schools to consider as well. Two geographical areas stand out as fundamental to the formation of the Western philosophical tradition, and those are Athens and Jerusalem, the tradition that comes from liberated rationality and human freedom, and the tradition that comes from piety and faith in God. These are the two strands of an intellectual braid which forms the history of Western philosophy, kind of like the intertwined snakes around the central staff in the symbol of the caduceus.

The traditions of Athens and Jerusalem form that kind of an intertwined legacy of the modern Western culture. The fundamental myths and conceptions of Western culture relating ethics to otherworldly metaphysics come out of Jerusalem, and the element of rationality and human-centered values comes out of Athens, the home of Socrates, the patron saint of rational inquiry. The Greek drive towards secular knowledge stands out in its time as unique among other traditions in the world that organized knowledge around myths.

4. The Role of logos in the Two Traditions

The two words to pay attention to in differentiating these two strands of philosophical history are logos and mythos. Logos (λόγος) is the Greek word for “reason”, and means rational discourse. The Socratic dialogues raise rational discourse to the level of an art form. An alternative conception of logos is the one in the New Testament. The Old Testament is written in Hebrew, and the Qur’an is written in Arabic; alone of the three sacred books of the Abrahamic tradition, the New Testament is the only one written in Greek, and it has the most affinities to Greek culture. The attempt to unify the two strands of Western culture from Athens and Jerusalem stemmed in large part from Christian intellectuals who by virtue of being able to read Greek had access to both traditions. Logos in the Biblical tradition does not mean “free, unfettered reason”, but rather means the “word of God” in the Book of John, meaning the authoritative, fundamental divine word of God. The fact that this same word is used by the two traditions to mean very different things has been the source of an endless amount of confusion and difficulties in the history of Western philosophy. But there is a point of connection between these traditions: perhaps there is something divine about free, unfettered human discourse.

5. The Role of Myth in the Two Traditions.

The second important word is that of mythos (μύθος) which is the Greek word for “story”. A myth is more than just a story, however, but it is an archetypal story that has universal applicability. Cast in the language of fiction, it nevertheless tells the truth. An example of such universal myths is the myth of Oedipus from Greek tragedy. These are not just rousing adventure stories, but rather they tell some universal truths about the human condition.

The tradition of Jerusalem also contains many myths, and one of Prof. Segrue’s favorites is that of Job, God’s faithful servant. The Book of Job is the highpoint of religious thinking in the Bible, in his opinion. He is the perfect example of religious piety, and because he is so obedient to God, God has blessed him with health, wealth, and a wonderful family. The Devil at some point makes an argument with God that the only reason why Job is obedient to God is in order to obtain the benefits which God has blessed him with; in other words, Job’s piety and obedience to God is really disguised self-interest. Therefore, the Devil argues to God, if you remove that blessing and curse him, Job will no longer be obedient to you. The Devil and the God therefore make a bet to see what Job will do.

God then sends down to Job a terrible series of catastrophes, his family is killed, his house and possessions are destroyed or lost, and then finally his health is destroyed by a series of diseases culminating in loathsome boils that cover his entire body. However, Job is completely faithful to God throughout this, the message being that we ought not to question God because he is so far above us as we are to earthworms. Job’s friends and his wife try to convince him otherwise, but he refuses to listen to them and instead is determined to steadfastly believe in God no matter what God sends his way.

A directly contrary myth from Greece is that of a man who does not

obey God, but rather disobeys him and that is the myth of Prometheus. He is not quite at the level of the gods, but aspires to be. He knows he his inferior to the gods, but nevertheless wants to improve himself and mankind to their fullest potential. He does not have humility and faith, but rather has pride and who shakes his fist in defiance at the gods, knowing full well that he will be punished for his act of disobedience but who doesn’t care.

Prometheus is a Titan who felt sorry for mankind because they didn’t have a lot of the advantages that others in the natural world had: they had no claws, or sharp teeth, or swiftness, or protective coloration. He liked human beings and, despite Zeus’ expressly forbidding him to bring man the divine spark of fire of the gods, Prometheus goes against Zeus in a way that parallels the Satanic will in Milton’s Paradise Lost which is responsible for the line “I would rather rule in Hell than serve in Heaven”. Prometheus is an important Greek myth because it expressed core Greek values. If you read the pantheon of gods as representing for the Greek imagination the forces of nature, Prometheus’ defiance of the gods is really the tale of the heroic taming of nature and blind chance. In Greek tragedy this defiance is called hubris, the overweening desire to become something more than what you were given at birth. This megalomaniacal pride is at the core of the Greek approach to the world.

The world of Job is a God-centered world, the world of Prometheus is a human-centered world. When we braid together the traditions of these two worlds, we have to ask ourselves which set of virtues we prefer to follow. The problem is that the human psyche is made up of a heterogeneous set of components, meaning that they are not all the same. There is a rational component, there is an emotional component, and there is a religious component built into our psyche or our mind. If we focus on one tradition to the exclusion of the other, we are locking ourselves into a partial worldview that is not satisfactory from a psychological as well as philosophical standpoint. Not all edifying philosophies start with the same assumptions and end up with the same conclusions. In fact, there are alternative assumptions and alternative conclusions which may well be contradictory among themselves, but when you start to contemplate them, you may be edified in different kinds of ways; it may improve different parts of your psyche. In other words, experiencing different kinds of thinking are good for you. Wittgenstein once said, “philosophical illnesses usually stem from a dietary deficiency,” meaning one’s intellectual diet may be deficient in examples. If we think about religious texts alone, we may be lacking in scientific or mathematical examples. Similarly, if we were extremely positivistic and organized our thinking solely around physics, mathematics, and formal logic, it may well be that questions of good and evil, and human destiny may escape us.

So Prof. Segrue pleads for the listeners to this series not to have the courage of your own convictions, but the courage to call those convictions into question, to ask yourself “what if I was wrong?” and “how would I know if I was wrong?” If you sincerely apply yourself to the tradition of both Athens and Jerusalem, you will maximize your ability to absorb what the entire intellectual tradition of Western Philosophy can offer you. If you don’t make the attempt to extend the reach of your assumptions and your conclusions, at least make the imaginative leap to think about what it might be like to believe in an alternative set of assumptions and conclusions. What would the pluses and minuses be?

An example of intellectual honesty would be if we were contemplating a certain philosophical issue; let’s call it issue XYZ. What would count as evidence for this proposition or against it? Are you willing to look for evidence in favor of both what you believe and what you do not believe? The intellectual honesty you bring to this discussion will determine how much you will get out of these philosophical works. After you absorb the message of both Athens and Jerusalem, it will be up to you whether that changes you in the world of action.

The next set of lectures in this series will start at the beginning of the Western intellectual tradition of philosophy with the pre-Socratic philosophers. They are the earliest examples of the Greek drive to create secular knowledge. We are indebted to these Greek proto-physicists for the foundations of science that were developed during the Renaissance and afterwards. The skeptical, rational element of the Greek tradition that was born at the time of the pre-Socratic philosophers has remained a vital part of the Western intellectual tradition and is very much alive in the present day.

Filed under: Uncategorized | Leave a comment »