In the last post, I dealt with the high-level review of the change request review process which can be summed up in the acronym ECHO (see previous post). In this post, I am summarizing the detailed processes that surround the change requests that are performed as part of the process 4.5 Perform Integrated Change Control.

I am indebted to the Rita Mulcahy’s PMP Exam Prep book for its clear statement of the process for change requests. What I have done is taken her high-level overview and made a summary in the table below. For those who want to get more detail, I strongly recommend that you buy her review book and use it to help prepare for the PMP exam.

What I’m doing is taking her detailed list on page 125 of her book and illustrating it with diagrams that show how the high-level overview in the last post is related to this more detailed description.

1. Change Request Workflow (overview)

The overall pattern is clear: Change Requests are made, and then approved or rejected as part of Integrated Change Control, and then for those that change requests that are approved, they are then implemented.

Fig. 1. Overall change management workflow

Here’s a little more detail about these steps:

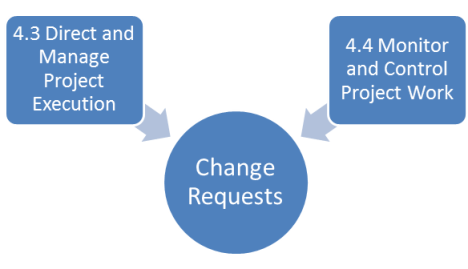

a. Change Requests

Change requests are generated, either as part of the process 4.3 Direct and Manage Project Execution in the Executing Process Group, or as part of the process 4.4 Monitor and Control Project Work. However, the need for changes to the project may be identified during other processes in the Executing Process Group, such as 8.2 Perform Quality Assurance, 9.4 Manage Project Team, or 10.4 Manage Shareholder Expectations, or ANY of the other processes in the Monitoring & Controlling Process Group. The changes may be identified by the project manager after he or she measures the project against the performance baseline, or it may be identified by other stakeholders such as project team members, sponsors, or customers.

b. Integrated Change Control

Once the change requests are created, they are inputs to the process 4.5 Perform Integrated Change Control. The approval can be done by the project manager (depending on his/her authority level and the magnitude of the change), the sponsor, or a change review board.

c. Implement Changes

If changes are approved as a result of the process 4.5 Perform Integrated Change Control, then outputs of that process are updates to the project management plan and project documents. The changes themselves are implemented back in the Executing Process Group under 4.3 Direct and Manage Project Execution.

2. Change Requests Workflow (Detailed)

Let’s take the first part of the workflow listed in Fig. 1 above involving the creation of Change Requests and expand it:

Fig. 2 Change Requests Workflow

a. Prevent changes

This is not an obvious step, but preventing changes is the most effective thing you can do on a project, even more than managing them when they occur. How do you do this? One of the main reasons for unexpected changes on the project is that the risk identification was not done thoroughly enough. So you try through risk management to do what you can to prevent the need for changes.

In fact, if a change occurs because of a previously identified risk event, one that has a risk reserve assigned to it, then that change should be handled as part of risk management, and not the change management process.

b. Identify changes

Okay, if you can’t prevent changes, the second most effective thing you can do on a project is identify them as early as possible. Why? The impact of a change increases as the project goes forward.

The need for a change may be identified by any stakeholder and during many different project management processes both in the Executing and Monitoring & Controlling Process Project (see paragraph 1.a above for details).

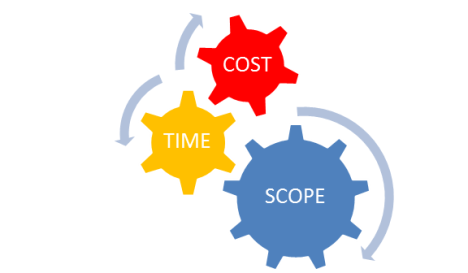

c. Evaluate the impact of the change

This is the “E” of the ECHO acronym mentioned in the last post. If the change affects one constraint, how will this affect the other constraints?

d. Create a change request

This change request is then sent on as an input to the process 4.4 Perform Integrated Change Control.

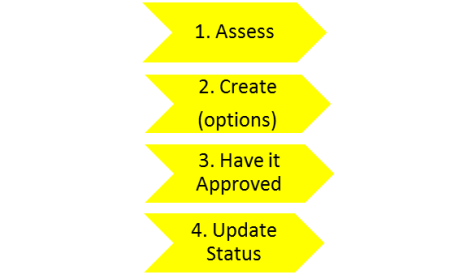

3. Implement Change Control Workflow

Let’s take the second part of the workflow above in Fig. 1 involving Implement Change Control and expand it:

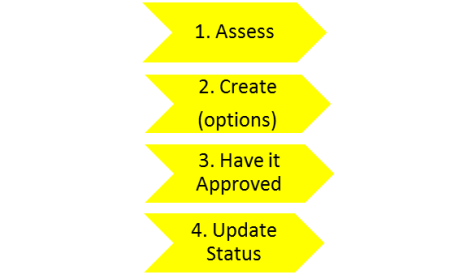

Fig. 3 Implement Change Control Workflow

a. Assess change

In a way, this is an extension of the E for Evaluate already done immediately upon identifying the change. The evaluate change process before meant investigating what the effect of this change in one constraint (scope, time, cost) will have on the other constraints. This is necessary because if the change will cost a certain amount of money to implement, this will effect who gets to approve the change in step 3.

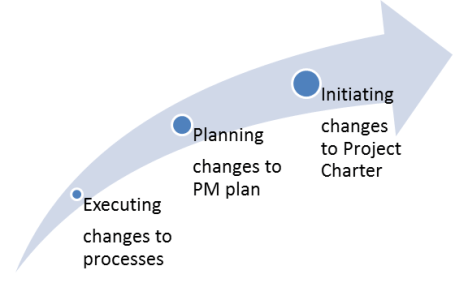

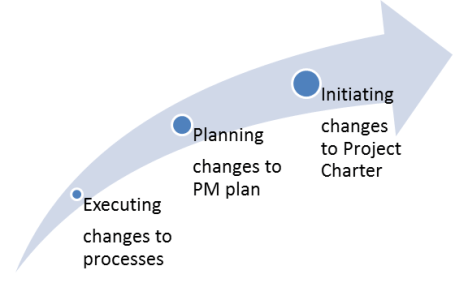

The assess change done in this step means seeing if the change involves changes to the following:

i. Changes to policies or procedures

Minor changes that would not affect the PM plan, but only change certain policies or procedures, would only involve implementing in the Executing Process Group.

ii. Changes to performance measurement baseline, PM plan

Moderate changes would involve going back into the planning process to re-calibrate the performance measurement baseline (scope, time, or cost baselin) or to update the project management plan. These would be implemented by updates to the PM plan in the Planning Process Group before the change themselves are implemented as part of the Executing Process Group.

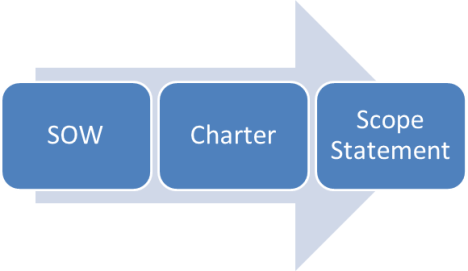

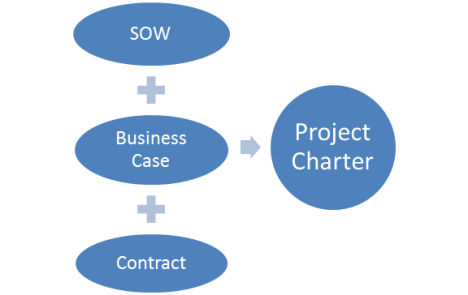

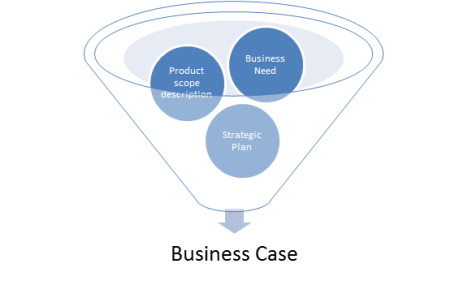

iii. Changes to project charter

Major changes that would change the product scope to the point that it would affect those high-level definitions in the project charter would be implemented by getting the updates to the project charter approved in the Initiating Process Group. It is possible that changes of this magnitude may not be approved, at which point the project comes to a screeching halt! If and only if they are approved, they then go on to change the PM plan in the Planning Process Group and then to implementation in the Executing Process Group.

Fig. 3a Levels of Magnitude of Project Changes

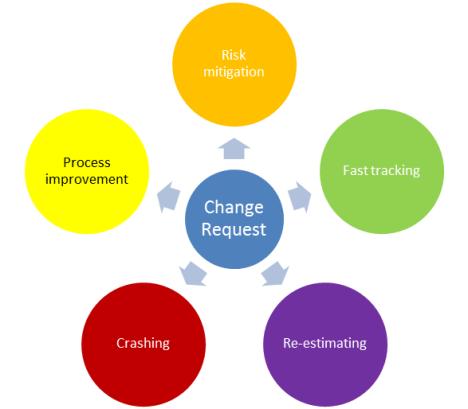

b. Create (options)

This is the “C” of the ECHO acronym from the last post. This is where options are considered on how to compress the schedule if necessary, how to perform the work involved in the change, or how to minimize the impact of the change. These options are presented along with the changes themselves to the change approval authority in the next step.

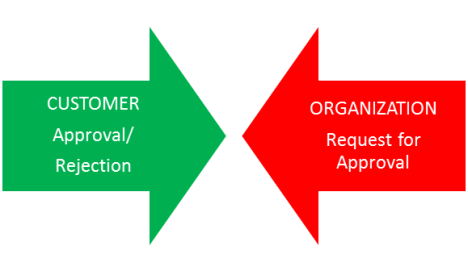

c. Have it Approved (by change approval authority)

In case of a minor change, the project manager may have approval authority. Otherwise, it will have to go to a sponsor or to a change control board. This is the “H” of the ECHO acronym from the last post. If the result of the project is to create a product for that customer, then you must okay it with the customer. This is the “O” of the ECHO acronym from the last post. However, in this case the change control board will already have the customer on it as a member, so this is also part of the same approval process.

d. Update Status

The status of the change is noted. If it is rejected, the reason is listed. Once a change is approved, it can then go and be implemented, noting that the implementation may be more complicated if the change is of greater magnitude (see diagram 3a above).

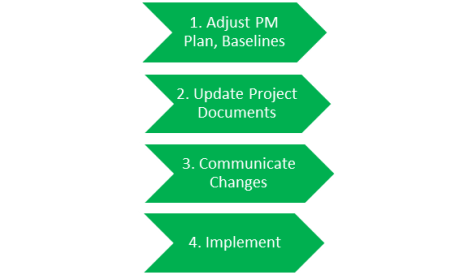

4. Implement Changes

Let’s take the third part of the workflow above in Fig. 1 involving Implement Changes and expand it:

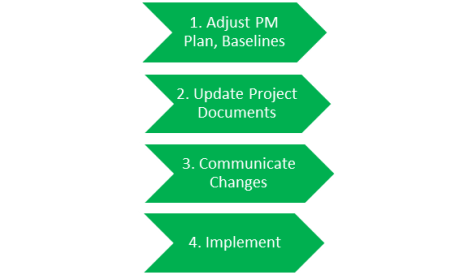

Fig. 4 Implement Changes Workflow

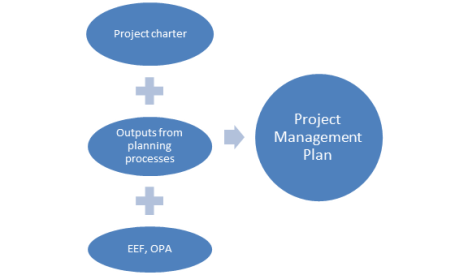

a. Adjust PM Plan, Baselines

If the change is moderate, that is, it changes the performance baselines or other aspects of the PM plan, then that plan needs to be adjusted before implementation can begin.

b. Update Project Documents

If the change to the scope is moderate, then the project scope statement, the scope baseline (project scope statement + WBS + WBS dictionary), and the requirements traceability matrix will have to be updated in addition the PM plan as part of the Planning Process. If the change to the scope is major, then the project charter will have to be updated, which means it will have to be re-approved as part of the Initiating Process Group. These different types of updates are covered in figure 3a above.

This changing of the project documentation can be considered part of configuration management. Once the changes to the project are done through the change management process, the configuration process takes over and manages changes to the deliverables and the project documentation.

c. Communicate Changes

All stakeholders affected by the change need to be informed of its configuration (this is project update 5.3.1, for example). This is part of configuration management, although it is part of communication management as well.

d. Implement Changes

After the changes are approved, documented, and communicated, then it is time to implement the changes in the Executing Process Group, specifically process 4.3 Direct and Manage Project Execution.

This concludes the expansion of each of the processes involved in creating, approving, and implementing changes requests.

The next post covers the last process in the Implementation Knowledge Area processs 4.6 Close Project of Phase.

Filed under: Uncategorized | Leave a comment »