The following are my notes from the lecture that was given by Prof. Richard Bulliet of Columbia University on January 17, 2009. In the next part of the lecture, Prof. Bulliet dismisses a theory comparing the difference in the evolution of nomadic societies centered on the horse vs. those centered on the camel.

4. Horse vs. camel nomads—a theory by Xavier de Planhol

This grassland was a pastoral nomadic zone using the native species of the horse. All of the world’s domesticated horses come from here, the two-humped camels come from Central Asia, one-humped camels come from Arabia, and donkeys come from Africa. The type of climate and topography and the type of animals have an impact on the ways that people organize a society.

There is one geographical theory, which Prof. Bulliet doesn’t think works, that says that nomads using horses can become great military powers because they have a greater density of population which is in turn caused by the fact that there is more vegetation in the horse zone. Camel nomads, on the other hand, can’t become great military powers because they’re more sparsely distributed. It’s a wonderful theory by the famous French geographer Xavier de Planhol except that it doesn’t actually coincidence with history, and therefore we won’t go into it.

5. Pastoral zones—a cultural buffer zone

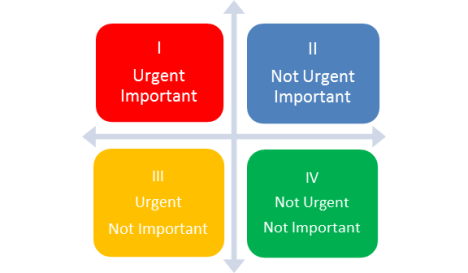

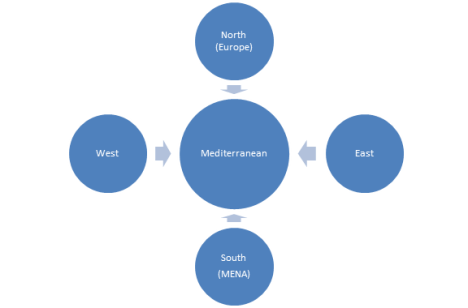

The reason why Prof. Bulliet is singling out these pastoral zones is because they provide a more important barrier than the physical boundaries to certain types of cultural movement. Pastoral nomads are, by the very nature of their dependence upon and reverence for their herds of animals, on the move on a very regular basis. This limits the material culture that they can develop. They don’t have cities; they often don’t have permanent settlements of any kind. They don’t have monumental artwork or things of that sort. They are more likely to develop cultural expression through song, poetry, and dance, through things that are inherently portable. They also live lives that are very abstemious. They do not have much in the way of luxury consumption. If you look at this Northwest Eurasian quadrant (see fig. 1), you will find that it is bordered by pastoral nomads in the south, and in the southwest including Iran, in the deserts to the east and the steppes directly to the north of them, which are also pastoral although not as dry as the deserts.

Figure 1. NW Eurasian quadrant aka the Mediterranean Basin

So you have a zone of settled agricultural lands and peoples that is blocked off to the east, the south, and the southeast by zones of pastoral nomads and arid lands. That Northwest Eurasian quadrant or zone is often described as the Mediterranean Basin, which Prof. Bulliet thinks puts more emphasis on the Mediterranean than it warranted. The name is somewhat realistic, however, because it does center on the Mediterranean, but it is a zone that looks inward (towards the sea). The culture in this zone tends to have a great deal of interpenetration and common features.

By contrast, when you get to the other side of the pastoral areas, whether it is sub-Saharan Africa or India or East Asia, you find dramatically different cultural patterns and internal patterns of cultural exchange and dissemination that don’t have much connection with what you have in the Northwest Eurasian zone. Prof. Bulliet thinks it is useful to think of this northwestern zone, hemmed in by pastoral nomadic life patterns, as being a single more or less unified or interconnected cultural zone throughout history.

6. Unity of Eastern and Western Mediterranean culture

This was apparent in ancient times and continues to be apparent to those who study ancient times. In other words, when you read Herodotus who lived in Greece, he speaks with Greek relations with Egypt or with Phoenicia; the connections of the north and south side of the Mediterranean are well understood. When Odysseus travels back from Troy (located in modern Turkey) he touches places in North Africa. When Aeneas goes from Troy, he goes to Carthage located in North Africa, and across the Mediterranean to Italy. The Romans fought the Carthaginians in three Punic Wars. The contacts in and around the seas of the Mediterranean were continuous not only in reality but in the imagination. In Greece, for example, you could imagine that Jason in the tale Jason and the Argonauts goes to the Eastern end of the Black Sea to collect the Golden Fleece and his charming wife Medea (laughter). Even though it was barbarian territory, it was considered within the realm.

As you looked northward, things were a little less clear. The north for the Ancient Greeks was the land beyond Mt. Borea, and the people were referred to therefore as the Hyperboreans, “above Mt. Borea”. The North was a little-known area whether it was whatever was north of Greece, or whatever was north of Italy and Spain. That was where you had people moving across the steppe land into Hungary along the Danube River and across northern Europe.

When you study these things and think about ancient history, you are in the field of classical philology, and it is assumed you study Greek and Latin. This is because it is recognized that almost all the sources that you’re going to have to read for the Eastern area (east of Italy) are going to be in Greek and those in the Western area (from Italy westward) are going to be in Latin. So we took about Greco-Roman antiquity, and we’re perfectly comfortable with that. Even though they are of the same language family and certainly closely related in the sense that you can take declensions and conjugations in Greek and see how they relate to those in Latin, they are written in different alphabets and create quite a different impression. Nevertheless they are all welded together in the studies we have of the ancient world, so we talk about Greco-Roman or Classical Antiquity. You have two different languages, two different writing systems, and in the course of time because of the division between the Eastern Christian church and the Western Christian church, you have a religious division. Nevertheless, it’s reasonable to fit it all together.

From both in the indigenous literary and cultural remains from this Northwest Quadrant, and in studies from ancient times onwards to modern times, it is considered perfectly reasonable to include the East and the West in the same cultural perspective.

7. Apparent Cultural Disunity of Northern and Southern Mediterranean culture

What happens is that, at a certain point, a line gets drawn horizontally through the Mediterranean Sea, and that line separates Christians from Muslims. That separation between Christians and Muslims is overwhelmingly an artifact of scholarship. After the death of Mohammed in 632, you have a series of Arab armies coming out of Arabia in the 600s and conquering lands in North Africa, the Middle East, and Iran, and reaching Pakistan at one extreme and Spain at the other extreme in 711. You have a political entity that is created that is called the Caliphate ruled by a Muslim ruler called a caliph. The people are almost all non-Muslims. Most of the Christians alive in the world at the time of the Conquest had great-grandchildren who were Muslims, because the most heavily Christian areas were conquered by the Muslims.

The remnant Christian areas in the South, such as Ethiopia, and Armenia and Georgia in the East, become more or less isolated. The other remnant Christian community is in Europe, in Greece, Turkey, Italy, Spain and southern France. That is the area that grows into the dominant force within Christendom over a period of centuries. Over that same period of centuries most of the people living under Muslim rule were still Christians. Conversion takes something of the order of 400 to 500 years. It is neither fast, nor organized. It is not an automatic product of the change in rule.

When you have scholars in modern times who have argued that, as soon as the Arab invasions occurred, you have a division between Europe and Islam that is complete, indissoluble, permanent, and hostile, that is an ideological construction. It does not coincide with what people thought at the time; it is not demonstrable in the documentation that survives. It is rather a reflection of later centuries in which you have periods of warfare and enmity between Muslims and Christians. You could say that periods of warfare and enmity automatically lead to permanent divisions, because how in the world can you go out and try to kill your neighbors because they have the wrong religion for a long period of time without permanently creating an unbridgeable gap between those two religions? The problem with that argument is that it simply doesn’t work; no two groups of people have ever hated each other as much as the Protestants and the Catholics (laughter), or have spent as much time trying to butcher one another and declare one another to be agents of the Devil. And yet, over time, things cool down and they say, “never mind–we don’t have to hate each other because we’re all Christians.”

The fact that Christians and Muslims went through periods of warfare only becomes central to the construction of a tremendous division IF the person who is making that construction is servicing other ideological needs, regardless of whether it is on the Muslim side or the Christian side.

8. Islamo-Christian Civilization

Prof. Bulliet is dedicated to the idea that we should think of this Northwest Quadrant of Eurasia as being an “Islamo-Christian Civilization” rather than a Christian civilization facing an enemy Muslim civilization. Prof. Bulliet says you can buy that idea or not, although you have to buy his book The Islamo-Christian Civilization because it’s one of the required texts for the course (laughter). You have to read the book, and then you can throw away the book if you don’t like the idea (laughter).

There is another division that gets included in this, and that is rarely talked about. In Euro-American thinking about “the West”, we commonly talk about Western Europe and Eastern Europe. Western Europe is the Industrial Revolution and the Enlightenment, John Locke, toleration and everything good. Eastern Europe is serfs, and thick-headed Slavs (laughter), and people who have funny alphabets like Cyrillic and Greek. It’s not like the West, but it’s still Christian, so we talk about Eastern Europe and Western Europe.

The odd thing is that, if you are living in the southern area of the Mediterranean, that area that we identify as being associated with Muslim populations, you also have the concepts of “the East” and the “West”. The East in Arabic is called the mashriq, from a verb sharaqa meaning “the sun rises” because the sun rises in the East. From it you have feel-good concepts like ishraq meaning “illumination” which gets into a spiritual sort of concept. By contrast, you have the maghrib, the Arabic term for “the West”; you could say it comes from a verb for the sun setting. But it is also a verb which means to be strange, weird, queer, or eccentric. Ghariib means “strange” or “wonderful.”

It is interesting that within the Islamic cultural context the West is the land of wonder and in the European cultural context the East is the land of wonder. So you have Orientalism in Europe, where you construct the East as a land of strangeness and wonder. However, there is no such term meaning “Occidentalism” such as istighrab or something similar in Arabic meaning “the construction of the maghrib as a place of strangeness”. When you read the histories that were written in early centuries of Islam about the West, there are full of fantasies and fairy tales and things that are not really believable as history, so the West becomes a kind of fantasy to some degree.

Here we have a situation where you have a West and an East in Europe and a West and an East in the Islamic world. They divide pretty much at the same place, that is to say, anything East of Italy is Eastern Europe–unless you’re directly above Italy and you have Central Europe, which is just an awkward concept altogether (laughter). Therefore Albania and Serbia on the Eastern side of the Adriatic Sea are part of Eastern Europe and Italy on the Western side of the Adriatic Sea is part of Western Europe.

When you divide the maghrib from the mashriq or the West from the East in the Islamic context, you really start due South of Italy with Tunisia. So Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco, are the maghrib. Is Libya part of the maghrib? Yes, it is part of the maghrib, but there are only 15 people living there throughout most of history (laughter), so it doesn’t really count a whole lot. Substantively, the maghrib was Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco and including the ancient province of Tripolitania, which was the Northwest province of modern-day Tunisia. The East was Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Iran, Turkey, and so forth.

In other words, this division between the West and the East in Europe is pretty much identical to the division between the Greek zone and the Latin zone in the ancient world. Even though you’ve changed religion over a slow process, and even though you’ve changed the political structure so you have at least nominally and briefly a single empire, you still have that old division between the East and the West, or the maghrib and the mashriq.

9. Political Division between East and West in Islamic World and in Europe

This actually plays out in politics as well. Even though you have this caliphate that is established in the 600s, by the early 800s the maghrib is no longer functioning as part of the caliphate. You have a family of governors in Tunisia known by the unattractive name of the Aghlabids (laughter), who asked the caliphate in Baghdad whether they could be the permanent governors in return for a yearly payment and he said “yes”. And from that time onwards from the early 800s Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria and Spain are separate from the Caliphate. Going in the other direction, at the same time southern Pakistan, which had been conquered by the Muslims, also becomes an independent area by agreement with the Caliph. The wings are cut off, and the center of Islam becomes the mashriq.

You have a parallel to this, of course, in what happened to the Roman Empire. Around the year 300, during the reign of Diocletian, you have the division of the Roman Empire into the Eastern Roman Empire and the Western Roman Empire, and you have a new city Constantinople (today Istanbul) which becomes the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, with Rome remaining the capital of the Western Roman Empire. The dominant language of Constantinople, even though it is part of the Roman Empire, is Greek. The dominant language of Rome is Latin.

What happens in the Caliphate, with the division between East and West, is what had happened 500 years earlier in the Roman Empire with their formal recognition of the division between East and West. The division between East and West is a more enduring geographical division when it comes to the Mediterranean Sea than the division between North and South. The division between North and South nowadays is often not only politicized, but is summarized as meaning “north of the Mediterranean” vs. “south of the Mediterranean.”

Note: I was intrigued by Prof. Bulliet’s theory of the cultural significance of the terms East and West, namely that the East is the land of the strange and unknown in Europe, whereas the West is the land of the strange and unknown in the Islamic World. As an example, notice how in J.R.R. Tolkien’s epic fantasy trilogy of The Lord of the Rings, the Shire, the familiar home of the Hobbits which opens the story told in the trilogy, is in the Western portion of Middle Earth, whereas the land of terrible danger called Mordor lies to the East. The cultural metaphors of East and West as conceived in Europe were still present, although J.R.R. Tolkien was creating a geography of a totally mythical country. If the Lord of the Rings had been written in the Islamic World, Mordor would have been described as being in the West and not in the East.

Map of Middle Earth from J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings

(image from http://www.glyphweb.com/arda/m/middleearth.html)

In the next portion of the lecture, Prof. Bulliet talks about how the assimilation of religious minorities during the Middle Ages proceeded differently in Europe as opposed to the Middle East.

Filed under: Uncategorized | Leave a comment »