I’ve been enthused about language learning all my life, but my discovery of Benny Lewis and his multilingual abilities at his website fluentin3months.com has really inspired me to expand my fluency in several languages. I started a premium-level subscription to his site last year to gain tips and tricks for how to become more fluent in the languages I’ve studied. I updated to his 2.0 version of his premium-level subscription in November, and the great content just got better.

1. Keeping Your New Year’s Resolution

One of the things he encourages those members of his community to do is to set out a plan on how they want to tackle a new language in the coming year. See his post on keeping a New Year’s Resolution with regards to learning a new language (or improving your fluency in one you already know).

How to Make a New Year’s Resolution and Actually Keep It

His main tips are:

- Create goals that are specific and measurable

- Allow yourself to feel a sense of accomplishment and progress

- Know your limitations and don’t let setbacks derail your momentum

- Use tools to track your progress

These tips are good for any goal, not just ones having to do with learning languages, by the way.

2. How to create specific and measurable language goals.

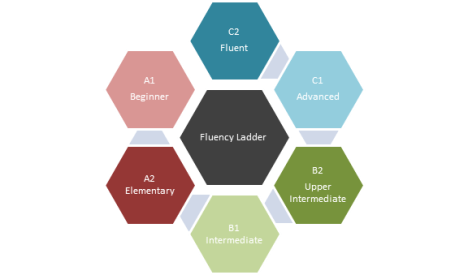

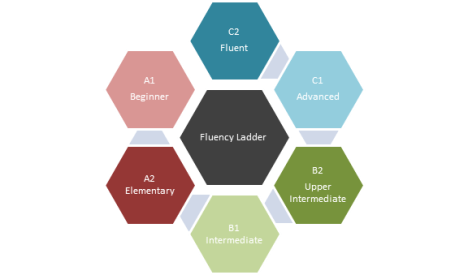

One way to measure your specific fluency level is to use the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages. There are six fluency levels, with A1, A2 being the levels needed to survive in a country, B1, B2 being the levels needed to live in a country, and C1, C2 being the levels needed to thrive in a country.

This framework has been influential worldwide because China’s proficiency exams have been changed to conform to this framework.

|

Level |

Explanation |

| A1 |

Beginner |

Can introduce oneself and understand familiar everyday expressions. |

| A2 |

Elementary |

Can describe oneself and communicate about one’s immediate environment. |

| B1 |

Intermediate |

Can talk about past and future events and about most situations encountered at work or school. |

| B2 |

Upper Intermediate |

Can communicate about simple ideas and concepts in a way that is generally understood. |

| C1 |

Advanced |

Can communicate about complex ideas and concepts in a way that is easily understood. |

| C2 |

Fluent |

Can summarize complex idea and concepts and create coherent presentations. |

So when you start to learn a new language, your first goal should be to reach the “A1” level. Once you’ve achieved that, you can go on to A2, etc. The rough rule of thumb is that is takes twice as much time to go to each higher level than the one before. How much time it takes to go up any particular level depends on a) your consistency, b) the difficulty of the language, usually measured by how far it is on the linguistic “tree” of languages from your own (so Chinese takes three times as much time per level as Spanish for an English speaker).

3. My Multilingual Plan

Last year around this time I put together a “multilingual plan for 2014.” Today I put forward my new plan for 2016.

Last year, I put down what my plan was for each language, but this year I’m doing things differently. I’m listening the language app, and then what languages I’m studying on it.

a. Duolingo

I’m using Duolingo to study various languages. I have languages that are on …

- high rotation (once a day): Spanish, French, German, Italian, Portuguese

- medium rotation (twice a week): Dutch, Danish, Irish, Swedish, Turkish

- low rotation (once a week): Norwegian, Ukrainian, Esperanto, Russian, Polish

For each language, I practice two skills which gives me 20 experience points (10 for each skill). For the high rotation languages, my goal is to finish the entire skill tree by the end of the year. This puts you at around B2 level fluency, and after that you go to the translation skill tree, which I first want to try with Spanish.

b. Memrise

The problem about Duolingo is that it doesn’t really handle languages very well that don’t use the Latin-based alphabet. So for Mandarin Chinese, Japanese, and Korean, I use this app once a day.

c. Foreign Service Institute, Defense Language Institute

Duolingo helps with vocabulary, and understanding individual utterances, but doesn’t help you memorize vocabulary patterns or gain fluency in conversation. For this I use the courses on Foreign Service Institute for the same courses that are in high rotation on Duolingo, namely, Spanish, French, German, Italian, and Portuguese. These I end up listening to about twice a week.

For Arabic, I had to turn to the Defense Language Institute recordings, because they not only have the general Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), but the Egyptian and Syrian dialects as well.

d. Rosetta Stone

I’m using this to study Arabic (MSA), because at the end of every other lesson you can have a 30-minute session with a native speaker to monitor your progress.

e. TBD

This year, I plan on taking the HSK (Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi) test for Mandarin Chinese. I have passed it at the B1 level and am working towards the B2 level. I think I will need to get a Chinese tutor for this, and I’m looking into various services that I can use.

How do I study all these languages at the same time? Well, I’m passionate about learning languages, and your mind is always creative in the ways it can find time for something you are passionate about!

- I subscribe to the List app, which helps you create and maintain daily habits through the power of social media. This helps you create a consistent practice: even if you study for only 5 minutes every day, this is better than studying 30 minutes every week! Benny Lewis recommends Memrise, which I now use on a regular basis.

- I listen to foreign language recordings while driving, in particular my language recordings from the FSI courses mentioned above.

- I listen to language recordings while doing housework. It takes away the drudgery of routine physical tasks by listening to foreign languages while doing it. You’ll reorder your brain while putting order into your environment.

- Finally, the proof of language learning is in the speaking, and I plan to find incorporate the learning of foreign languages through Benny Lewis’ Conversation Partners and through professional teachers at Italki.

These are some creative ways I try to use my time so that I can do something as audacious as to follow Benny Lewis’ lead, whom I mentioned at the beginning of the post. My goal is to gradually move up in all of the languages I’ve already studied, while using Duolingo to introduce myself to new languages at the very basic level. Learning languages exercises the brain, and it provides you with a unique form of empathy towards the various cultures of the world. Let’s see how far I can go in 2016!

Filed under: Uncategorized | Leave a comment »