I am starting a project of going through the 6th Edition of the PMBOK® Guide and blogging about its contents. The 6th Edition was released on September 22nd by the Project Management Institute, and the first chapter is a general introduction to the framework in which project management exists, starting with section 1.2 Foundation Elements (section 1.1 describes the purpose of the Guide).

The section I am going over in this blog post is section 1.2.6 Project Management Business Documents. These are two documents which are inputs into the first project management process 4.1 Project Charter. If these are inputs into the first project management process that are created even before the project is initiated, then where do they come from? They are actually outputs of Business Analysis, and so they are essentially the intersection between Business Analysis and Project Management.

The two project management business documents are:

- Project business case–this is an economic feasibility study which demonstrates the benefits or business value to be created as a result of the project

- Project benefits management plan–describes how the benefits created as a result of the project will be maintained after the project is done

The project business case should be a familiar document to PMPs, because it was described back in the previous edition of the PMBOK® Guide. However, the document that is new for the 6th Edition of the Guide is the project benefits management plan. In this post I will cover the project business case.

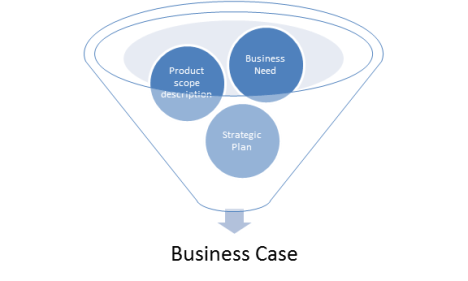

Here are the main elements of the business case.

- Product scope description–There is a description of the product, service, or result that is being proposed to be produced by the project. This answers the question “What” objective is the project going to create.

- Business need–what is the benefit or business value that is going to be created as a result of the project. This answers the question “Why” is the project going to create its objective–from the standpoint of the stakeholder who will receive the benefit of the project.

- Strategic plan–what strategic goal or objective that will be achieved by doing the project? This answers the question “Why” is the project going to create its objective–from the standpoint of the organization doing the project.

These elements are combined in the project business case document as indicated in the graphic above. (Please note that the downward motion of the elements as they get processed together in the business case is NOT indicative of any editorial comment on my part that the project is going down the drain, or any other similar conclusion.)

It is important to distinguish the business need and the business case, because the terms are similar. The former is the reason for the project to be done; the latter is the document that explains why it should be done.

There are additional details that can be included in the project business case, and these are listed on p. 31. These are much more elaborate than those listed in the previous edition of the Guide, which shows the increasing importance PMI is placing on this document.

The question that the project business case answers is “what benefit or business value will be created by the project?” However, how does an organization make sure those benefits are not as temporary as the project? That is the purpose of the project management benefits plan, the other business document that is an input to the Develop Project Charter project, and it is the subject of the next post.

Filed under: Uncategorized | Leave a comment »