This post gives an overview of the first of the six planning processes in the Time Management Knowledge Area, with summaries of the inputs, tools & techniques, and output of the process.

1. Inputs

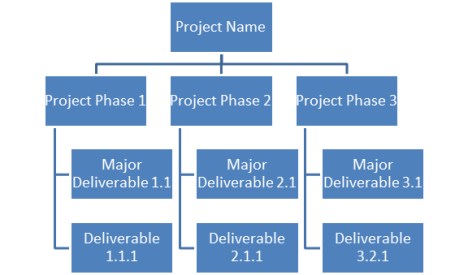

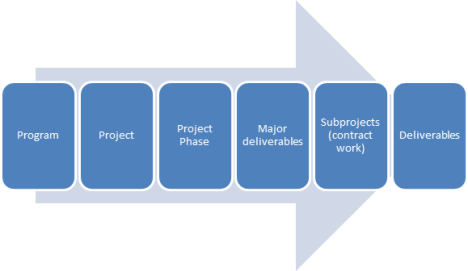

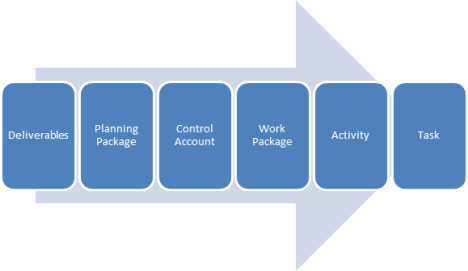

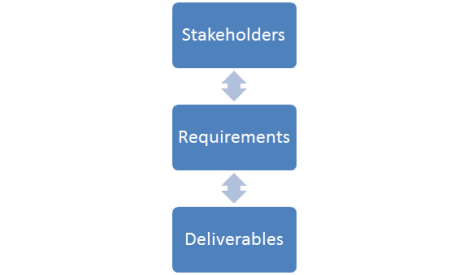

As far as inputs are concerned, the most important ones are the scope baseline, because that represents the work that needs to be done, and the schedule will tell you how much time is required to do it. Other knowledge management plans may provide input as well, some of which are completed after the schedule management plan in the list of planning processes. This shows that the planning process is iterative and may require several passes through in order to integrate the various knowledge area management plans.

The project charter will give the high-level time constraints and the list of critical milestones to be achieved on the project, some of which may actually be tied to project approval requirements (i.e., the project may absolutely have to be done within a certain amount of time).

The main EEF or Enterprise Environmental Factor is probably going to be the project management software used to create the schedule; the main OPA or Organizational Process Asset is probably going to be the historical information on prior similar projects that can be used to help estimate the schedule.

| 6.1 PLAN SCHEDULE MANAGEMENT | ||

| INPUTS | ||

| 1. | Project Management Plan | The following elements of the PM Plan are used in the development of the Schedule Management Plan:

|

| 2. | Project Charter | Summary milestone schedule, project approval requirements (particularly those dealing with time constraints). |

| 3. | EEFs |

|

| 4. | OPAs |

|

| TOOLS & TECHNIQUES | ||

| 1. | Expert judgment | Uses historical information from prior similar projects and adapts it appropriately to the current project. |

| 2. | Analytical techniques | Used to choose strategic options related to estimating and scheduling the project: |

| 3. | Meetings | Planning meetings are used to develop the schedule management plan. |

| OUTPUTS | ||

| 1. | Schedule Management Plan | Establishes the criteria and the activities for developing, monitoring and controlling the schedule. |

2. Tools & Techniques

Expert judgment and meetings should be familiar by now as typical techniques that project managers of creating something as complicated and intricate as a schedule. The analytical techniques that can be used with specific reference to the schedule are such methods as:

- Schedule compression (fast tracking or crashing)

- Rolling wave planning

- Leads and lags

- Alternatives analysis

- Reviewing schedule performance

UPDATE: Based on some comments, I wanted to add that the analytical techniques are not actually used in this process, because the schedule itself has not been developed (that takes place in process 6.2 through 6.6). What the Schedule Management Plan can do is LIST the options for tools & techniques that can be used later on in those scheduling processes. Sometimes details can be given in terms of under what conditions they will be used, what scheduling software or other tools to be used in conjunction with those techniques, etc.

3. Output

Finally, the output, as you could probably guess by the title of the process, is the Schedule Management Plan. Let’s take a closer look at the contents of the Schedule Management Plan in the next post to see all that goes into it, and how these contents relate to the other project management processes in the Time Management Knowledge Area.

Filed under: Uncategorized | 4 Comments »