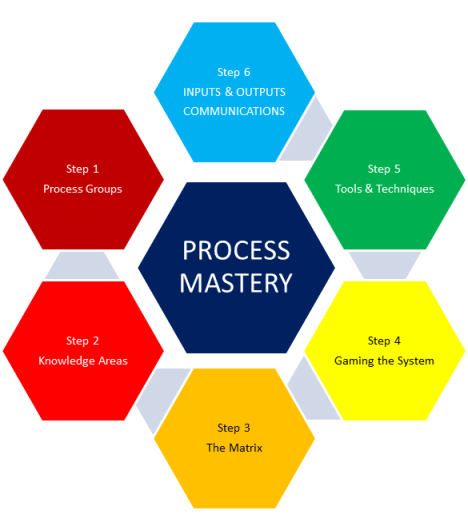

In this next series of posts on memorizing the processes, we move on to the final step 6, which is memorizing the INPUTS & OUTPUTS associated with each of the 47 processes. In order to breakdown the memorization into more bite-size chunks, I am breaking down the processes in the 10 knowledge areas into 2 or 3 posts each.

This post covers chapter 12 of the PMBOK® Guide, which covers the Procurement Knowledge Area. This knowledge area contains 4 processes, one in the Planning Process Group, one in the Executing Process Group, one in the Monitoring & Controlling Group, and one in the Closing Process Group. The Procurement Knowledge Area is the only knowledge area other than the Integration Knowledge Area to have a process in the Closing Process Group.

I am splitting the discussion of the Inputs & Outputs into two different posts, each covering two processes. This post will cover Process 12.1 Plan Procurement and Process 12.2 Conduct Procurements.

2. Review of processes 12.1 and 12.2 together with their ITTOs (Inputs, Tools & Techniques, Outputs)

The purpose of process 12.1 Plan Procurement is to create the Procurement Management Plan, which gives the framework needed to document project procurement decisions, to specify the approach to procurement, and to identify potential sellers.

The purpose of process 12.2 Conduct Procurement is to obtain seller responses to the request for proposal (RFP) or another form of procurement request, to select a seller based on established criteria, and to award the procurement contract to that seller.

As usual, in the list of inputs, I use abbreviations for the generic inputs of Enterprise Environmental Factors (EEFs) and Organizational Process Assets (OPAs).

| Process Name |

Tools & Techniques |

Inputs |

Outputs |

| 12.1 Plan Procurement |

1. Make-or-buy analysis

2. Expert judgment

3. Market research

4. Meetings |

1. Project management plan

2. Requirements documentation

3. Risk register

4. Activity resource requirements

5. Project schedule

6. Activity cost estimates

7. Stakeholder register

8. EEFs

9. OPAs |

1. Procurement management plan

2. Procurement statement of work

3. Procurement documents

4. Source selection criteria

5. Make-or-buy decisions

6. Change requests

7. Project documents updates |

12.2 Conduct Procurement

|

1. Bidder conference

2. Proposal evaluation techniques

3. Independent estimates

4. Expert judgment

5. Advertising

6. Analytical techniques

7. Procurement negotiations |

1. Procurement management plan

2. Procurement documents

3. Source selection criteria

4. Seller proposals

5. Project documents

6. Make-or-buy decisions

7. Procurement statement of work

8. OPAs |

1. Selected sellers

2. Agreements

3. Resource calendars

4. Change requests

5. Project management plan updates

6. Project documents updates |

3. Outputs of process 12.1 Plan Procurement and 12.2 Conduct Procurement

a. Procurement management plan (12.1 Plan Procurement)

The Procurement Management Plan, like the Risk Management Plan, has elements that touch upon practically all of the other knowledge areas. I have taken the list of elements of the Procurement Management Plan listed in the PMBOK® Guide and arranged them by related knowledge area in order to put some structure to this rather large list of elements.

|

Related Knowledge Area |

Plan Element |

| 1. |

Integration |

Project constraints and assumptions that could affect planned procurements |

| 2. |

Scope |

Direction to sellers on developing and maintaining work breakdown structure (WBS) |

| 3. |

Format for procurement statement of work (SOW) to be put in contract |

| 4. |

Time |

Coordination of procurement with project scheduling |

| 5. |

Handling long lead times to purchase certain items from sellers and coordinating extra time needed with project schedule |

| 6. |

Linking make-or-buy decision with Estimate Activity Resources and Develop Schedule processes |

| 7. |

Setting scheduled dates for delivery and acceptance of contract deliverables |

| 8. |

Cost |

Whether independent estimates will be used as evaluation criteria |

| 9. |

Quality |

Performance criteria for acceptance of deliverables |

| 10. |

Human Resources |

Roles and responsibilities for project management team coordination with the organization’s procurement or purchasing department |

| 11. |

Communications |

Coordination of procurement with performance reporting |

| 12.. |

Risk |

Risk management issues related to procurement |

| 13. |

Requirements for performance bonds or insurance contracts to mitigate project risk |

| 14. |

Procurements |

Types of contracts to be used (fixed price, cost-reimbursable, or time & material) |

| 15. |

Identifying pre-qualified sellers |

| 16. |

Procurement metrics to be used in evaluating sellers and managing contracts |

| 17. |

Management of multiple suppliers |

| 18. |

Stakeholder |

Include sellers as one of stakeholder groups to be managed |

| 19. |

EEFs |

Industry or professional organization information resources regarding potential sellers |

| 20. |

OPAs |

Standardized procurement documents |

b. Procurement statement of work (12.1 Plan Procurement)

The Procurement Statement of Work (or Procurement SOW) is a critical component of the procurement process. It can be considered to be the “seed” of the procurement, and it provides suppliers with a clearly stated set of goals, requirements, and outcomes from which they can provide a quantifiable response. For the elements of the Procurement statement of work, see paragraph p. below under Inputs.

c. Procurement documents (12.1 Plan Procurement)

There are different documents which are used to formally request procurements, among which are the following types:

- Request for Information (RFI)

- Invitation for Bid (IFB)

- Request for Proposal (RFP)

- Request for Quotation (RFQ)

- Tender Notice

- Invitation for Negotiation

- Invitation for Seller’s Initial Response

Specific procurement terminology used may vary by industry and location of the procurement.

d. Source selection criteria (12.1 Plan Procurement)

Used to rate or score seller proposals. Selection criteria may be as narrow as simply the purchase price and the cost of delivery if the procurement item is “off-the-shelf”, or readily available from a number of acceptable sellers. For more complex products, the following may be used as source selection criteria:

- Understanding of need (does the seller’s proposal address the Procurement SOW?)

- Overall or life-cycle cost (including purchase cost and operating cost)

- Technical capability (does the seller have the technical skills and knowledge required?)

- Risk (how much risk is embedded in the SOW?; how much risk will be assigned to the seller?; how does the seller mitigate risk?)

- Management approach (does the seller have management processes and procedures to ensure a successful project?)

- Technical approach (does the seller’s technical methodologies meet the procurement document requirements?)

- Warranty (what does the seller propose to warrant in the final product, and for what period?)

- Financial capacity (does the seller have the necessary financial resources?)

- Production capacity and interest (does the seller have the capacity and interest to meet potential future requirements for production?)

- Business type and size (does the seller’s enterprise meet a specific category of business set forth as a condition of the agreement award such as a small business?)

- Past performance of sellers (what has been the past experience with selected sellers?)

- References (can the seller provide references from prior customers?)

- Intellectual property rights (does the sellers assert IP rights in the work processes or services they will use or in the products they produce for the project?)

- Proprietary rights (does the sellers assert proprietary rights in the work processes or services they will use or in the products they produce for the project?)

e. Make-or-buy decisions (12.1 Plan Procurement)

This output is the result of the technique of make-or-buy analysis that is used as part of process 12.1 Plan Procurement.

f. Change requests (12.1 Plan Procurement and 12.2 Conduct Procurement)

A decision to procure rather than to produce certain goods, services, or results to be used on the project requires a change request. As with all other change requests, it then becomes an input to process 4.5 Perform Integrated Change Control, where the change request is reviewed and either accepted or rejected.

g. Project documents updates (12.1 Plan Procurement and 12.2 Conduct Procurement)

The particular project documents that may be updated as part of the process 12.1 Plan Procurement or 12.2 Conduct Procurement are:

- Requirements documentation

- Requirements traceability matrix

- Risk register

- Stakeholder register

h. Selected sellers (12.2 Conduct Procurement)

The list of selected sellers is one of the main outputs of the 12.2 Conduct Procurement process. Selected sellers have been judged to be in a competitive range based on the evaluation of their proposals or bids.

i. Agreements (12.2 Conduct Procurement)

A procurement agreement can be called any of the following:

- an understanding

- a contract

- a subcontract

- a purchase order

It contains the terms and conditions for the procurement. The project management team must make sure that all agreements not only meet the specific needs of the project, but that they also adhere to the organization’s procurement policies.

j. Resource calendars (12.2 Conduct Procurement)

Includes the quantity and availability of contracted resources, as well as the dates on which each specific resource will be actively used on the project.

k. Project management plan updates (12.2 Conduct Procurement)

The following elements of the Project Management Plan may be updated as part of the 12.1 Conduct Procurement process.

- Performance baselines (cost, scope, and schedule baselines)

- Communications management plan

- Procurement management plan

4. Inputs of process 12.1 Plan Procurement and 12.2 Conduct Procurement

a. Project management plan (12.1 Plan Procurement)

Although the PMBOK® Guide lists the Project Management Plan as an input, to be more accurate, the most relevant portion of that overall plan to the 12.1 Plan Procurement process is the scope baseline, which consists of

- Project scope statement–contains product or scope description (or alternately a service description or result description), the list of deliverables, acceptance criteria, technical issues that could impact cost estimating, and project constraints (such as required delivery dates, available skilled resources, and organizational policies)

- WBS (contains the components of work that may be resourced externally)

- WBS Dictionary (provides an identification of the deliverables and a description of the work in each WBS component)

b. Requirements documentation (12.1 Plan Procurement)

The requirements documentation may include

- Product requirements that are considered during planning for procurements

- Contractual and legal requirements (related to concerns about health, safety, security, performance, environmental, insurance, intellectual property rights, equal employment opportunity, licenses, permits)

c. Risk register (12.1 Plan Procurement)

Provides the list of risks, along with the results of risk analysis and risk response planning.

d. Activity resource requirements (12.1 Plan Procurement)

Contains information on specific needs such as people, equipment, or location.

e. Project schedule (12.1 Plan Procurement)

Contains information on required timelines or mandated delivery dates.

f. Activity cost estimates (12.1 Plan Procurement)

Used to evaluate the reasonableness of the bids or proposals received from potential sellers.

g. Stakeholder register (12.1 Plan Procurement)

Provides details on the project participants and their interests and impacts on the project.

h. EEFs (12.1 Plan Procurement)

The EEFs that are inputs to process 12.1 Plan Procurement include the following:

- Marketplace conditions

- Products, services or results that are available in the marketplace

- Suppliers, including past performance or reputation

- Typical terms and conditions for products, services or results for the specific industry

- Unique local requirements

i. OPAs (12.1 Plan Procurement and 12.2 Conduct Procurement)

The OPAs that are inputs to process 12.1 Plan Procurement include the following:

- Formal procurement policies, procedures, and guidelines–most organizations have units dedicated to procurement, but when such procurement support is not available, the project team needs to supply the resources and the expertise to perform such procurement activities.

- Management systems–considered in developing the procurement management plan and selecting the contractual relationships to be had.

- An established multi-tier supplier system of prequalified sellers based on prior experience on previous projects

j. Procurement management plan (12.2 Conduct Procurement)

This input is the main output of process 12.1 Plan Procurement Management. See paragraph a. above under Outputs for a complete listing of the elements of the Procurement Management Plan.

k. Procurement documents (12.2 Conduct Procurement)

Provides an audit trail for contracts and other agreements.

l. Source selection criteria (12.2 Conduct Procurement)

These can include information on the following aspects of the supplier:

- Required capabilities

- Capacity

- Delivery dates

- Product cost

- Life-cycle cost

- Technical expertise

- Approach to the contract (Fixed-Price, Cost-Reimbursable, or Time & Material)

m. Seller proposals (12.2 Conduct Procurement)

Prepared in response to a procurement document package, the seller proposals form the basic information that will be used by an evaluation body to select one or more successful bidders (sellers).

n. Project documents (12.2 Conduct Procurement)

The risk register may include risk-related contract decisions.

o. Make-or-buy decisions (12.2 Conduct Procurement)

Factors that may influence make-or-buy decisions are:

- Core capabilities of the organization

- Value delivered by vendors meeting the need

- Risks associated with meeting the need in a cost-effective manner

- Capability internally compared with the vendor community

p. Procurement statement of work (12.2 Conduct Procurement)

The procurement statement of work may include the following elements:

- Specifications

- Quantity desired

- Quality level

- Performance data

- Period of performance

- Work location

The next post will cover the last two processes of the Procurement Management Knowledge Area, process 12.3 Control Procurements and 12.4 Close Procurements.

Filed under: Uncategorized | Leave a comment »