In John Stenbeck’s book “PMI-ACP and Certified Scrum Professional Exam Prep and Desk Reference”, he creates an “agile project management process grid” which describes 87 processes used in agile project management. These processes are divided into five process groups (Initiate, Plan, Iterate, Control, and Close), which are analogous to the five process groups in traditional project management, and seven knowledge areas which can be mapped, more or less, onto the ten knowledge areas in traditional project management.

I am now covering processes that are performed during the Control process group of an agile project. Remember, after the Planning process group, an agile project does not go in a linear fashion from Iterate to Control to Close; rather, it cycles from Iteration to Iteration with periodic checkpoints (many times at the end of an iteration cycle) where you Control or make changes to a project to make sure it gets back on track. Or sometimes, you even change the track itself if there is a change in the requirements.

In the past set of posts, I have covered those processes done in the Control process group that relate to the fourth knowledge area of Team Performance. Today I start covering processes related to Risk Management:

- 5.11 Obstacle Removal

- 5.12 Variance and Trend Analysis

- 5.13 Escaped Defects

The first of these is 5.11 Obstacle removal, which I covered in the previous post; I cover 5.12 Variance and Trend Analysis.

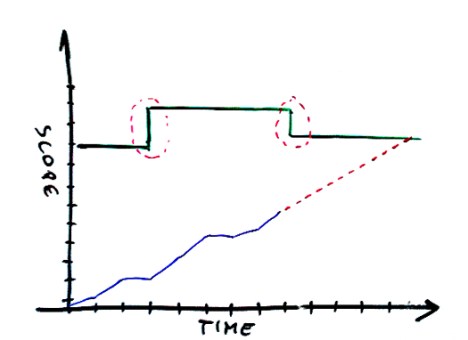

Variance analysis calculates the difference between actual and estimated levels of performance and analyzes the cause or causes of the differences in order to be able to correct them.

Trend analysis collects data points, including those concerning the level of performance, and analyzes them to detect patterns that may predict the future trajectory of these data points.

Do you remember the Christmas Story by Charles Dickens, where Ebenezer Scrooge was visited by the ghosts of three spirits: the Ghost of Christmas Past, the Ghost of Christmas Present, and the Ghost of Christmas Future?

In a project, a project manager or scrum master is also haunted by three ghosts, but in this case they are called the Ghost of Defects Past, the Ghost of Defects Present, and the Ghost of Defects Future.

The Ghost of Defects Past is covered in the next process 5.13 Escaped Defects. This post deals with the other two Ghosts: the Ghost of Defects Present, and the Ghost of Defects Future.

The Ghost of Defects Present is detected through variance analysis, and the measures taken to exorcise this ghost are called corrective actions.

The Ghost of Defects Future is detected through trend analysis, and the measures taken to exorcise this ghost are called preventive actions.

The best tool to use for variance and trend analysis in agile projects would probably be the burn-down chart. The burn-down chart shows both the team’s planned and actual work, so it is easy to compare the actual work delivered against estimated work planned.

We will discuss the process 5.14 in the next post on Escaped Defects.

The next process 5.12 Variance and Trend Analysis will be discussed in the next post.

Filed under: Uncategorized | Leave a comment »