In John Stenbeck’s book “PMI-ACP and Certified Scrum Professional Exam Prep and Desk Reference”, he creates an “agile project management process grid” which describes 87 processes used in agile project management. These processes are divided into five process groups (Initiate, Plan, Iterate, Control, and Close), which are analogous to the five process groups in traditional project management, and seven knowledge areas which can be mapped, more or less, onto the ten knowledge areas in traditional project management.

This post concerns the process of controlling agile contracts that were entered in process 2.3.

An agile contract is one that is designed for an agile project management environment. In my last post, I discussed the three different types of contracts in traditional project management to give a contrast to the agile contracts discussed in this post.

Traditional PM Contract Types

As a recap, here are the three types of contracts used in traditional PM.

Three Types of Contracts in Traditional PM

The three types of contracts in traditional project management are:

- Fixed price

- Time & material

- Cost reimbursable

In terms of cost risk, you can list the three types of contracts in the following way, where a higher cost risk to the seller is to the left, and a higher cost risk to the buyer is to the right.

Fixed Price –> Time & Material –> Cost Reimbursable

Fixed price contracts tend to be used when the scope is predictable, and thus a fixed price is readily obtained for the component. Cost reimbursable contracts, on the other hand, are used for when the scope is NOT so predictable, and thus the cost of the component cannot be so readily obtained.

Inherent in the fixed price and cost reimbursable contracts are the tension between the seller and buyer in terms of cost risk; fixed price favors the seller and cost reimbursable favors the buyer. That is why there are mechanisms in place (ceiling price, incentive fee, etc.) to make the cost risk more equitable on either side.

Agile Contracts Types

In agile contracts, on the other hand, all three types try to balance the cost risk between seller and buyer, and the difference comes to not how they are structured in terms of cost, but how they are structured in terms of time. Agile iteration contracts are done for the duration of an iteration. Time & Material contracts are done for an arbitrary period of time. Phased development contracts are done on a quarterly basis.

One feature that agile contracts have in common with traditional PM contracts is that they tend to be risk management tools. In the case of traditional PM, the focus is primarily on cost risk.

- Agile Iteration Contract–this is based on each team delivering agreed upon features to defined quality standards by iteration end. NOTE: The Product Owner is NOT allowed to change the iteration backlog DURING the iteration.

- Time & Material–this is based on a customer continuing to pay a customer during an agreed-upon time period until such point that the customer doesn’t see value being added, at which time the customer stops paying and the contract ends.

- Phased Development–this is based on the team achieving a successful release of the product.

In agile contracts, cost risk is a factor as well, and the time period of the contract is chosen based on the needs of the customer and the size of the project, but the agile contract helps manage other areas as well. Here is a chart showing how the four areas of scope, risk, communication, and cost management (related to issues of invoicing and payments) are dealt with in the three types of contracts listed above.

| CONTRACT TYPES |

Agile Iteration |

Time & Materials |

Phased Development |

| Scope Management |

Mutual, based on team delivering agreed upon features to defined quality standards. |

Dependent on customer seeing continued value. |

Funded quarterly following each successful release. |

| Risk Management |

Mutual, using product backlog grooming and iteration backlog commitments. |

Customer carries change management risk; budget may be used up w/o achieving expected value. |

Mutual, limited to one quarter’s development costs. |

| Communication Mgmt. |

Project scope confirmed at the start of each iteration. |

Interdependent need to actively prevent dissatisfaction. |

Interdependent need to secure additional funding. |

| Cost Mgmt. |

Can be a T&M or Earned Value agreement, usually with cost ceilings. |

Invoice sent after agreed-upon work period, may include cost ceilings. |

Invoicing is paid within funding limit, with iteration contract addendums. |

The overall point to remember with agile contract is that the relationship between the customer and team is paramount; the contract is merely a formalizing of that relationship and a way of dealing with risks that may occur in the future so that the customer and team can essentially put them aside and focus on their working relationship in the present.

Controlling Agile Contracts

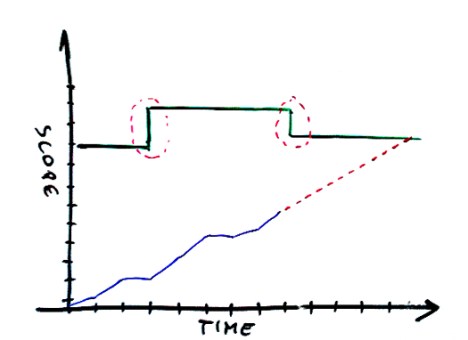

The first word that should come to mind when thinking of the word “controlling” in project management is the companion word “monitoring”. First you monitor to see if the contract is being carried out as planned, and then if it isn’t, THEN you control the situation, either bringing it in line with the contract or modifying the contract as necessary.

The key point is that, just with traditional project management, a contract divides the shared risk between the parties and thus defines what the pressure points of trust are between them.

The best practice in monitoring a contract is to define a small number of high level user stories that include acceptance criteria that are the conditions of satisfaction for each story. The conditions of satisfaction need to be discussed during the process 2.3 so that the development risk can be seen as adequately being covered and equitably being shared in the course of the agreement.

Any effort spent defining the conditions of satisfaction will pay for itself in the time and cost avoided having to mitigate any undefined requirements later.

Another element of good contract control is good estimating, so that both parties can realistically determined the amount of risk each party is sharing.

Periodically monitoring the contract is not questioning the trust of the parties; it is building a solid foundation so that such trust can be built upon during the course of the project.

The next post covers the issue of earned value management in agile projects.

Filed under: Uncategorized | Leave a comment »