This series of posts take the Ken Wilber’s introduction to Integral Theory called A Brief History of Everything and discusses the 12 main tenets concerning the concept of a holon and how they can be applied to the field of project management. I have been posting one tenet a week on Sundays; this post covers tenet #8.

1. Recap–definition of a holon, and tenets #1-7

A holon is an entity which consists of components, and yet is itself a component of a larger whole.

Tenet #1. Reality as a whole is not composed of things or processes, but of holons.

Holons must be considered from the standpoint of interacting with other holons on the same level, and with holons at higher levels (of which the holon is just a part) and lower levels (which comprise the parts of the holon).

Tenet #2 Holons display four fundamental capacities: The horizontal capacities of self-preservation, self-adaptation, and the vertical capacities of self-transcendence and self-dissolution.

Holons follow the dual rules of evolution when it comes to holons at the same level: survival of the fittest (self-preservation) and survival of the fitting (self-adaptation). Holons have the property of being able to evolve to the next highest level (self-transcendence), and they can also “devolve” into their component parts (self-dissolution).

Tenet #3 Holons emerge

As mentioned in Tenet #2, holons have the property of self-transcendence or evolution to the next highest level. This is not just a higher degree of organization, but also involves emergent properties or differences in kind from the level below.

Tenet #4 Holons emerge holarchically

Holons, as seen above, are units that are both wholes containing parts and parts of larger wholes. This kind of nested or concentric linking of holons reminiscent of the Russian matroshka dolls is considered a holarchy. In contrast, we see in an organizational chart the traditional notion where parts are linked vertically to the levels above them (the notion of hierarchy), and horizontally to the units at the same level (the notion of a heterarchy).

Tenet #5 Each emergent holon transcends but includes its predecessor(s)

When a higher level of holons emerges, it incorporates the holons from a lower level but adds emergent properties. A cell contains molecules, but is an entity which is capable of reproduction, where a property that goes above and beyond what a mere collection of molecules could do on its own.

Tenet #6 The lower sets the possibilities of the higher; the higher sets the probabilities of the lower.

Tenet #5 tells us that the higher level of holon has emergent properties which go above and beyond the lower level. However, tenet #6 says that the higher level cannot ignore the lower level, and it there is bound to a certain extent by the possibilities set by the holons of the lower level. However, the higher level also affects the lower level in that, the order imposed by the higher level of holons will influence the patterns in which the lower levels interact.

Tenet #7–The number of levels which a hierarchy comprises determines whether it is “shallow” or “deep”; and the number of holons on any given level we shall call its “span.”

The word for a hierarchy that is formed, rather than like an organizational chart by a series of horizontal and vertical lines, but rather by a concentric series of levels or organization better represented by circles, is called a “holarchy.” At each level, the measure of the horizontal dimension, that is, the number of holons at that level, is called its “span” in the terminology of Integral Theory. Now, the number of levels in the vertical dimension, on the other hand, is called its “depth”. This is the number of levels of the holarchy, or concentric organization, that the holon is a part of. The complexity of a project comes from its “depth”, not its “span.” Bigger (in terms of span) is not always better.

In an aerospace company, a project will have a “span” equal to however many project members are involved in the project. Its “depth” will be determined by whether, going upwards, it is part of a program and/or portfolio, and going downwards, whether there are sub-projects that are outsourced to a supplier. The project manager has to manage not just the project, but has to be aware of the sub-projects that get integrated into the project as components purchased from suppliers, and in the other direction, of the program and portfolio of which that project is merely a part.

2. Tenet #8 Each successive level of evolution produces GREATER depth and LESS span

This tenet follows from tenet #7 if you think about the definition of “depth” and “span” of a concentrically organized system of a holarchy. Let’s say you have 5 projects that have been decided to be coordinated together in terms of a program in order to share resources between projects. Before you had a “span” of 5 and a depth of “1”, meaning that at the project level, there were 5 projects in total, and only 1 level, that of the project itself. After adding coordinating the projects in terms of a program, at the program level there is a “span” of 1 and a depth of “2”, meaning that there is only 1 program (consisting of the 5 projects) and two levels, that of the program and the projects which comprise it.

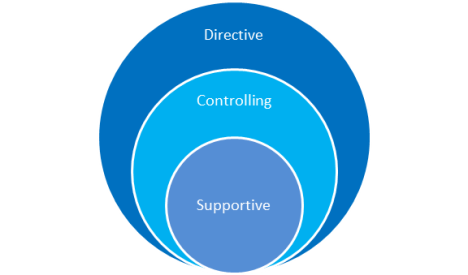

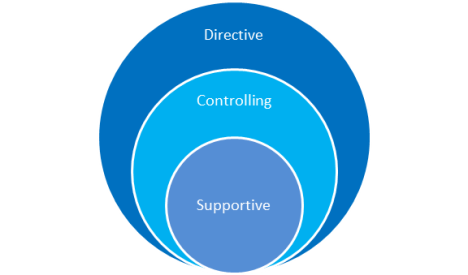

This may seem kind of a trivial point, that there will be fewer programs than there will be projects, because the programs each consist of several projects. Ken Wilber makes this point because if you look at the concentric diagrams of any holarchy, the circle containing the highest level of organization is going to be on the outside, and the visual impact is that it has greater “span” in terms of area. So Ken Wilber is simply emphasizing the fact that span refers to the number of holons at the same level; the reason why the circle is so large is so that it can encompass the lower levels inside of it. The fact that the largest circle, representing the holon at the highest level, has several circles within it actually means that it has the greatest depth because it includes the most levels or holons (represented by the nested series of circles inside of it).

3. Coordinating Complexity: The Example of a Project Management Office

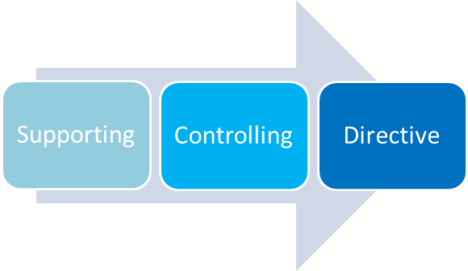

Because of the different levels of coordination needed between the subprojects (e.g., components outsourced from suppliers), projects, programs, and portfolios of an organization, many larger organizations have Project Management Office that oversees all of the project work in an organization (as opposed to the ongoing operational work) through all of its levels. It is, in effect, one more layer of complexity or, using Integral Theory terminology, a level of holon above even the portfolio level itself. There are three types of Project Management Organization or PMO, Supportive, Controlling, and Directive each of which has an increasing degree of control over the entire set of projects, programs, and portfolios in an organization. The arrow below is in the direction of increasing control:

and a description of the 3 types of PMO is as follows in the chart below:

| |

PMO Type |

Degree of Control |

Description |

| 1. |

Supporting |

Low |

Consultative role for projects. Supplies templates, best practices, training, access to lessons learned on previous projects. |

| 2. |

Controlling |

Medium |

Support and compliance role for projects. Supplies templates, best practices, etc. and assures compliance through audits. |

| 3. |

Directive |

High |

Managing role to projects. Supplies templates, best practices, assures compliance through audits, and directs completion of projects. |

Take a look at the description of the Supporting type of PMO. It consults on the projects, and acts as a repository of knowledge based on projects that have come before. This already benefits the organization by having a centralized place where the various templates, guidelines, training materials, and lessons learned from previous projects can all be stored for reference by any project manager in the organization.

The next level of control comes from a Controlling PMO, which adds to the supportive role in terms of a repository of knowledge, and also makes sure that the project managers are actually utilizing the best practices which they should be getting from that repository of knowledge through audits.

The final level of control comes from a Directive PMO, which adds to both the supportive and controlling role and actually takes a direct role in the execution of projects. The project manager not only accesses the repository of knowledge built up by the PMO, but the processes which the project manager follows are audited, and the results are monitored and controlled as well.

For those who have been following Integral Theory in these posts, you will recognize that the three types of PMOs themselves form a concentric series of levels of organization, and are themselves an example of a holon.

A friend of mine who is on the board at a chapter of the Project Management Institute was hired as a project manager by an organization, and when they saw her experience, they wanted to get her input on the feasibility of creating a PMO within the organization. Their vision of the PMO was in the form of a Directive type of PMO, which would actually monitor and control the results of all the projects. They wanted to develop this first, but she said that the other levels, the supportive and the controlling levels of the PMO, needed to be developed first. You can’t monitor and control the results of all the projects effectively without first making sure the project managers are using the project management processes correctly (the Controlling function of a PMO), and you can’t in turn make sure the project management processes correctly if the project management does not have access to all the knowledge and training required to know what the correct processes are.

They wanted the PMO to have one level, the Directive level, without having the “depth” that a PMO needs to have at that level, meaning that it has to ALSO have the Controlling and Supportive functions established. Her instinct I believe was a correct one, and I wish her well in her quest to communicate that to her organization.

The next post in the series (one week from today) will cover tenet #9.

Filed under: Uncategorized | Leave a comment »